Politics and society reflected all this tumult. The conversations at Wortley Hall touched on the decline of class politics, new conceptions of identity more complex than the hoary category of “worker”, how an insurgent women’s movement had highlighted huge changes to the fabric of everyday life, the rising importance of green politics, the increasing expectation of personal autonomy – and how seemingly unstoppable forces were weakening the traditional nation state. While the right had turned these changes to its advantage, far too much of the left still lived in a world that was fast disintegrating beneath its feet. As one Marxism Today editorial put it, the Labour party and the trade unions were “profoundly wedded to the past, to 1945, to the old social-democratic order … backward-looking, conservative, bereft of new ideas and out of time”.

Union membership was declining fast. By 1988, Labour had lost its third consecutive election to Thatcher’s Conservatives. The party had moved on from the unapologetic old-school socialism that it had presented to voters in 1983 and painstakingly worked on more modern policies and presentation, but in retrospect, its thinking was still largely built around enduring articles of traditional socialist faith. Labour people still believed that Thatcher’s success amounted to a flimsy con-trick – and it was Labour’s job, as their 1980s leader Neil Kinnock put it in one of his impassioned conference speeches, to “deliver the British people from evil ”. The means of doing so still revolved around the big, beneficent, centralised state, the promise of stability and security through paid employment, and the idea that people’s identity could usually be boiled down to their lives as workers.

Three decades later, the impact of the economic and social changes that Marxism Today identified is undeniable – and the politics it prescribed are, if anything, more relevant today than ever before. But apart from a few cosmetic updates, today’s Labour party still essentially clings to the same old shibboleths. Indeed, with the election of Jeremy Corbyn, its collective faith in them looks to have been renewed. Just before the last general election, Corbyn assured one interviewer that his was “a class-based socialist party”; throughout the recent leadership campaign, he extolled the wonders of nationalisation and at one point suggested that some British coal mines might be reopened. Meanwhile, centre-left politics all over Europe remains locked in a deep crisis, sidelined by the dominance of the centre-right, and further unsettled by the rise of new populist and nationalist parties from both ends of the political spectrum. In the delirium of Corbynmania and the arrival of tens of thousands of new members, the cold reality of Labour’s predicament has been somewhat forgotten. At the last election, it won its second-lowest share of the vote since 1983.

In leftist circles today, one frequently hears the argument that the world was changed for ever by the crash of 2008. But a much older point has still to be satisfactorily answered: has the left ever really understood the consequences of the economic and political changes that began to reveal themselves in the 1970s, defined the 1980s, and have been hugely accelerating ever since? On the evidence of his pronouncements over the last 30 years and the messages he dispensed during the leadership campaign, Corbyn does not seem to. Even Blair and Brown, who were at pains to stress their understanding of the late 20th century, failed to convincingly remodel their party’s politics for this new age.

This is the case for the continued relevance of a magazine that published its last issue in 1991. As this summer’s Labour leadership election showed, there is a need for a modern, radical politics, more ambitious and forward-looking than either reheated New Labour or a revived hard left. But it is nowhere to be seen – and that absence arguably sits at the heart of the Labour party’s ongoing crisis, and the sense that the left, here and across Europe, is all at sea.

***

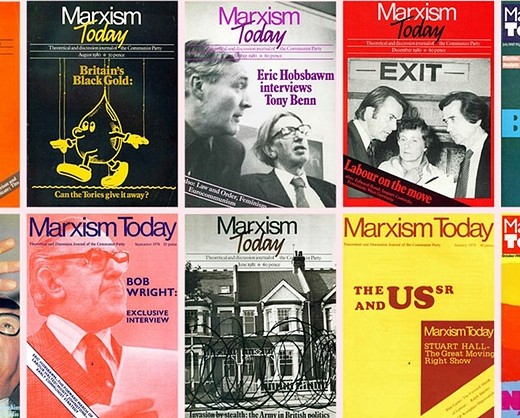

For most of its life, Marxism Today – founded in 1957 – described itself as “the theoretical and discussion journal of the Communist party”. But in its peak period – from 1977 to 1990 – it was far from what those words suggested. Though published from inside the belly of the Communist party of Great Britain (CPGB), it spoke to a whole swath of the British left, and particularly the Labour party. Moreover, what it said was not academic and abstract, but vivid and urgent.

These were convulsive times. A run of watershed events began with Thatcher’s first election victory in 1979, and the 1980 arrival in the White House of her ideological soulmate, Ronald Reagan . After austerity and recession, the Falklands war came in 1982, ensuring another Thatcher election win a year later. British coal miners began a year-long strike in 1984 and were defeated in 1985; the printworkers who took on Rupert Murdoch began a similarly doomed struggle in 1986. The same year, the Thatcher government abolished England’s Metropolitan County Councils, and the Greater London Council (GLC) , and thereby snuffed out a loud municipal revolt led by Labour politicians; a year on, the Conservatives won a third Westminster term. In 1989 came the most seismic change of all: European Communism breathed its last , and the free-market politics championed by Thatcher and Reagan was proclaimed triumphant.

Such were the birth pangs of a new order, as an innovative kind of accelerated capitalism spread across the planet. In the everyday world, this transformation took the form of a turbocharged consumerism, so that as old certainties collapsed, the world was suddenly painted in deep and dazzling colours. Marxism Today captured the mood: I read it avidly as a politics-obsessed teenager, and in my memory, its bold, brazenly modern covers sit in the same place as the 1980s’ iconic record sleeves.

As Britain and the wider world were transformed, the magazine set out on a journey based on three big ideas. One, the work of the renowned historian and lifelong Communist Eric Hobsbawm, was a clear diagnosis of the crisis that had confronted Labour and the trade unions. Another was a prescient analysis of Thatcherism, a term invented by the Jamaican-British thinker Stuart Hall , and used to describe not just a political project, but its embedding in millions of ordinary lives in the form of basic ideas about common sense and everyday life. When the magazine’s thinkers subsequently came up with what they called the “New Times” project, they wrapped up these previous insights in an all-encompassing analysis of profound changes, running much deeper than politics.

By the 1970s, the British Communist party was almost irrelevant as an electoral force, but its senior members included high-ranking trade unionists, and its organisation was partly built around a national network of shop stewards. Its offices in Covent Garden were bugged by MI5; its daily paper, the Morning Star, came out each day, buoyed by a Soviet subsidy in the form of up to 15,000 copies bought each day, and flown out to the USSR. The party’s once-rigid orthodoxies had been shaken by the Soviet invasions of Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968 – and the latter episode in particular had galvanised a young generation of Communists intent on pushing their politics somewhere new, in defiance of the pro-Soviet diehards known as “tankies”, in honour of the military vehicles that had rolled into Budapest and Prague. One of these activists was Martin Jacques – a native of Coventry, the son of Communist parents, a graduate of Manchester University, and by 1967, a member of the party’s executive committee.

I met Jacques, now 69, in his mansion-block apartment nudging Hampstead Heath, where we sat in his kitchen, talking over the endless gurgle of a fishtank and drinking green tea. He was preparing for one of his regular trips to China, the global power he analysed and explained in his bestselling 2009 book When China Rules the World , but he happily cast his mind back to the passions that had driven him nearly 50 years ago, when his life was changed by the student militancy that spread across Europe in 1968. In Manchester, he and other students were embracing the more political aspects of the 1960s counterculture – but his perspectives were decisively shifted when he spent a week in and around Prague, two months before the Russians arrived. “I know what I thought then. I can remember it vividly. I basically said: ‘Everything is contingent now, and how things relate to my membership of the CP” – he paused – “I don’t know .”

By the mid-1970s, British Communists of Jacques’s ilk had an increasingly clear sense of who they were. Their big theoretical inspiration was Antonio Gramsci , the Italian Communist who had died in Mussolini’s jails, and left a political legacy built around the concept of “hegemony” – in essence, the means by which capitalism maintains its dominance through culture, social institutions and the everyday stuff of supposed common sense, all of which would have to be turned around by a politics much more creative and outward-looking than the European left had so far managed. Gramsci’s devotees now looked not to the USSR, but Italy, where the national Communist party was blazing a trail for the open, nuanced and self-consciously “Gramscian” politics increasingly known as Eurocommunism.

In the CPGB, Eurocommunism began to amass momentum and influence, and just before the party congress of 1977, Jacques was approached by the party’s general secretary, Gordon McLennan – a representative of what Jacques characterises as the Communist party’s “centre ground”, whose politics were dutiful and dull, rather than sharply ideological. McLennan had an offer: would Jacques give up his life as an academic at Bristol University, start a new working life at the CP’s offices, and edit Marxism Today? He would be paid the “party wage” of around £8,000 a year, and take his place in a small office partly staffed by volunteers.

Jacques recalled how his new job initially worked. “When I started, there was Doris Allison, who was 82, and like this – ” he walked around the table, bent double – “and she was in charge of subscriptions. There was Minnie Bowles, who was my part-time secretary. She was 75: a very sexy woman of 75. She just had something about her. And there was Margaret Smith, who would put in a day or half-day every week, and she was 65. Effectively, I was on my own. And that was the beginning of a new start.”

***

In three months spread across 1978 and 1979, Marxism Today published the two essays that started to set out a new mission for the British left. The Forward March of Labour Halted? appeared in September 1978. The work of Eric Hobsbawm, then in his mid 60s, it was initially delivered as the Communist party’s annual Marx memorial lecture. By modern standards, it was a somewhat pedestrian read, but its message was clear enough: if the Labour party and wider labour movement had understood themselves to be hopefully trudging onwards and upwards, their progress had long since stalled, as class consciousness had waned and Labour’s support had started to dwindle. There had been a superficial increase in union militancy in the 1970s, but most of it had been about increasing wages rather than heightening class consciousness. “It seems to me,” Hobsbawm wrote, “that we are now seeing a growing division of workers into sections and groups, each pursuing its own economic interest at the expense of the rest.”

The growth of white-collar employment and the mass entry of women into paid work were both part of this fracturing; in 1979, a third of the UK’s trade unionists would vote for Thatcher. “The forward march of labour and the labour movement, which Marx predicted,” Hobsbawm told his readers, “appears to have come to a halt in this country about 25 to 30 years ago.”

The second watershed text that Marxism Today published was a piece titled The Great Moving Right Show , written by Stuart Hall, the pioneer of cultural studies who would become Marxism Today’s most insightful thinker, and one of Jacques’s closest friends. Written in the somewhat chewy language of cultural and political theory, it was an analysis of what had been quietly happening to politics – and Britain at large – since the 1960s, and which was now being taken to a new level by Thatcher, despite the fact that she was still keeping her brand of zealously free-market economics somewhat hidden.

Hall knew that what the Tories were doing was much more ambitious than simply ramping up orthodox Conservatism: he talked about their new use of a “rich repertoire of anti-collectivism”, which fused with “popular elements in the traditional philosophies and practical ideologies of the dominated classes”. Thatcher and her allies, in other words, were living out Gramsci’s ideas about hegemony, by pursuing their politics on the terrain of common sense: kitchen-table economics, the comforts of self-sufficiency, the necessity of property ownership.

As well as coining the word “Thatcherism” six months before Thatcher had even taken power, he wrote about “the doctrines and discourses of social market values – the restoration of competition and personal responsibility for effort and reward, the image of the over-taxed individual, enervated by welfare coddling, his initiative sapped by handouts by the state”. And he identified something at the heart of Thatcherism that would serve the Tories well for the next four decades: “in the image of the welfare ‘scavenger’,” he said, the new Conservatives had hit upon “a well designed folk-devil”.

Hall and Hobsbawm quickly came to define Marxism Today’s intellectual core. According to their old comrades, they were as different as could be: Hobsbawm an imposing, exacting Communist whose debates with others would evoke “the weight of history”; Hall a more open operator who was never a member of the CPGB (“he did have an ego, but he was very willing to let people speak, and listen – he gave people permission to do their thing”). But in some Communist circles – and beyond, in left-wing academia, the Labour party and the trade unions – the pieces they wrote provoked the same controversy. In the New Left Review, the stentorian Marxist academic Ralph Miliband – the father of two sons who would eventually speed to the top of the Labour party – charged them with retreating into “new revisionism ”, and contributing “in no small way to the malaise, confusion, loss of confidence and even despair which have so damagingly affected the left in recent years”.

“Thatcherism was widely rejected when we first came up with the idea,” Jacques told me. “Tony Benn said: ‘Nonsense, it’s just the same old Toryism, but tougher.’ There was that cautious, conservative thinking which was unable to respond to change in the real world.” What he said next applied to what happened in the 80s, but he phrased it in the present tense. “One of the biggest problems is, the Labour party can’t think. And it never really has been able to think, of its own accord.”

Hall called the magazine’s detractors “the pessimists”: people who seemed to think “that we mustn’t rock the boat, or demoralise the already dispersed forces of the left”. He responded to them by quoting an injunction from Gramsci: “to address ourselves ‘violently’ towards the present as it is ”.

Beatrix Campbell was another important voice within MT’s pages. A fiercely clever, ideas-hungry Cumbrian and another child of Communist parents, she had come to London to live in a commune, and met and married a musician and journalist called Bobby Campbell. He was a folk violinist and boxing correspondent for the Morning Star, and he encouraged his wife to work for the paper, first as a subeditor and then a reporter. In 1970, she had her first encounter with the women’s liberation movement, at a meeting in Hackney: “I can see the people in the room as if it was now. Being in a room full of women, which was unprecedented … the allure was awesome.” She and other feminist members of the party started a new feminist journal titled Red Rag; when the CPGB leadership insisted they needed official permission, they carried on regardless.

Having been repelled by the loud sexism of some of the Morning Star’s senior staff, Campbell worked first for the London magazine Time Out, and then City Limits, the co-operatively run challenger founded by former Time Out staff after that magazine was forced to abandon its collective model of working. Thanks to her journalism, she became closely acquainted with the “metropolitan radicalism” Ken Livingstone was exploring at the GLC until the Thatcher government abolished it in 1986, and a strand of Labour politics that obviously intersected with what Marxism Today was saying. The GLC had an Industry and Employment unit, which not only involved itself in some of the capital’s businesses, but tracked the kind of economic changes the magazine was interested in. One MT article captured the way the politics of the GLC had taken root beyond the usual structures of the Labour party, in myriad “community papers, women’s groups, trade-union support units, peace groups, legal advice centres … [and] tenants groups”, and said that the council “has tried to see itself as giving strength to … the innumerable groups from which [its politics] sprung”. As Campbell saw it, “the genius of Livingstone was that he read London brilliantly: he saw that class was only one dimension of being a Londoner who was dispossessed. If you only had a class agenda, you didn’t get it.”

Campbell was recruited as a writer by Jacques, and eventually given her own column, titled Bea-Line (for which, after some negotiation, she was paid). Among her commissions was a March 1987 interview with the infamous Tory minister Edwina Currie : “She was up for anything – looser, more open-minded and more connected to popular culture than a lot of Tories would be. And she was shameless. And the thing that was great about that time was saying, ‘You’ve got to talk to Tories, to find out why they’re thinking what they’re thinking.’ The labour movement didn’t do that.”

There was always a tension in Campbell’s relationship with Marxism Today. “The MT boys were not interested in feminism,” she said. “Martin absolutely never got it … Stuart [Hall] didn’t really get it. Hobsbawm didn’t get it.” Nonetheless, the magazine gave space to feminist writers, and as it exploded leftwing orthodoxies, there was a sense of common ground. “For us, the death of socialism was its sexism – that was a catastrophic part of its history. So there was this funny convergence: we were writing about that, and the way that British Labourism produced a politics dedicated to inequalities, at the same time as Hobsbawm delivered The Forward March of Labour Halted? From a different direction, we were addressing the same problem.” The result, she said, was that “I felt like a Marxism Today person. I was terribly proud to be involved in it. It was so engaged, and restless. And thinking, thinking, thinking.”

Throughout the 1980s, Jacques and his writers carried on unsettling the left, in often delicate circumstances. Tempers were frayed by Marxism Today’s occasional habit of giving space to dissenting voices from the eastern bloc. In 1981, a leading British Communist called Monty Johnstone went to Poland, and came back with not only an interview for Marxism Today with the deputy prime minister, but also a smuggled-out cassette on which he had recorded a conversation with Lech Walesa, the leader of the insurgent Solidarity movement (“I am not a good politician. I am first of all a consumer and I want something to consume,” Walesa said – probably not the most welcome words to Communist ears). Twelve months later, Jacques ran an article by the renowned dissident Roy Medvedev, which triggered a letter from the central committee of the Communist party of the Soviet Union – to the more orthodox high-ups at the British party, the equivalent of an intervention from the headmaster – which, Jacques told me, “complained bitterly about it”.

In the same issue, there was an article that took another candid look at the increasingly troubled predicament of the trade unions, and drew fire from the old-school Communists at the Morning Star, who published a piece calling it “a gross slander on the labour movement”. The ensuing controversy gives a good flavour of the grim comedy of 1980s Communist politics: motions decrying Marxism Today were passed by the party’s London district secretariat and East Midlands district committee; the Action Rail trade union ranch complained about “the latest outrage to our class”.

Jacques believes the stink was kicked up at the behest of the Russians. “I think these guys were in cahoots with the Soviets. And for me, that was the beginning of the end. I thought: ‘The CP has had it.’” Soon after, in fact, the Morning Star was effectively captured by his adversaries, moved out of the Communist party’s control, and confirmed for keeps as the voice of a staunchly traditionalist, hard-left, union-based position (which – against not inconsiderable odds – it retains to this day).

Amid these factional battles, Jacques managed to remain focused on the magazine to which he was devoting most of his waking hours. Almost none of Marxism Today’s writers were paid, but he insisted that most pieces were rewritten two or three times – though if that seemed unnecessarily arduous, he could always point to the travails of his own existence. “Basically, my life was lived in a state of permanent emergency. That was what I felt like. It was like camping. No money, working all the hours god sends. I got ill on several occasions. ME-type illness. The first time was ’83, the second time was ’85. The worst was ’87. I was knocked out for a lot of ’87. I was in a state of total exhaustion. Money can buy you a weekend away, or a quick holiday, or a bit of fun, and we didn’t have any. And then there were all these incessant attacks. At the core of it all, there was this total devotion to creating a great magazine, and getting the best writers, and getting the most interesting ideas. That was my life.”

Julian Turner was a Cambridge graduate and CP member who was briefly Marxism Today’s production editor, before he became its business manager, at the new Communist party offices near Smithfield market in London. “It felt very exciting,” he told me. “It was a little island of youth in the CP building. There were about a dozen people permanently there, but that would expand to many more when we needed envelopes to be stuffed, or the magazine to be sent out, or whatever. Then you’d have this army – I don’t want to make out that our motives were anything other than intellectual and political, but usually extremely attractive people would arrive, and end up socialising afterwards, which was definitely part of the attraction.”

“Everybody that was employed on the magazine was on the party wage. The party wage was the same for everybody. It was £8,600 when I started. I think it went up to £9,800 – that may have been the peak. One of the formative experiences of my life was standing up in front of the party congress, and asking them to let me pay the advertising staff commission. How did that fit into their utopia? I had to explain why it was an equitable idea, and why it was pragmatic, and worth doing. We got that through.

“I think a lot of people at the magazine had very mixed feelings about Marxism Today,” he went on, “because they were able to develop themselves professionally to a very high standard, and they grew a lot of their skills. But it was very exploitative, I think. Martin is quite unforgiving: he’s not an easy person to work with. I would spend some time repairing the human damage that was wrought by pursuing a quality standard that we all believed in, but struggled to stick to. We had a lot of people who over-committed; who felt that the demands made on them were unreasonable.”

Suzanne Moore , the Guardian columnist whose journalistic career decisively began when she edited the back section of the magazine, which she renamed “Culture”, echoed these memories when we met in a pub near her north London home. “It was Martin’s magazine, and there wasn’t a word in it that didn’t go through him,” she told me, as she recalled long days spent at MT’s office. “He would phone me up at 4am. It was not a normal job. Because it wasn’t a job to him. It was a way of life.” She lasted six months as a member of staff, before she simply stopped going into the office, and even then was confronted with Jacques’ exacting approach to people-management. “He’d come round to my house on his bike and try and get me out of bed.”

***

By 1988, Marxism Today was attracting huge attention and selling around 20,000 copies a month, partly thanks to the fact that it was stocked by WH Smith. To some extent, it had turned itself into what Jacques called “the intellectual forum for the Labour party – I didn’t approach it like that, but that’s what it became”. A handful of senior Labour figures – Bryan Gould, a former academic who served as Neil Kinnock’s shadow industry secretary and in-house intellectual, was the best example – made a point of appearing on its pages, and the impression that Kinnock was busy modernising the party was boosted by the energy and attention Marxism Today had generated, as well as sympathetic coverage in its pages (in October 1984, one MT cover had simply featured a Kinnock headshot and the words “the face of Labour’s future”).

As the magazine’s success increased, there was talk about changing its title. “It was a problem,” Jacques told me. “But, you know, changing the name is quite tricky. And it became a joke: ‘Marxism Today? The only Marxism is in the title.’ Very early on, one of the designers said to me, ‘Why don’t you slowly reduce the size of ‘Marxism’, and increase the size of ‘Today’?” The arrival of the Today newspaper in 1986 killed that suggestion. “Another idea was to call it ‘MT’, but there was another magazine called Marketing Today.”

An altogether bigger concern was to do with the magazine’s momentum. “By this point, I thought we’d run out of steam a bit, really.” Jacques told me. “We were influential, but I thought we needed a fresh impulse. And there had to be fruit on the trees: we needed some new writers.”

So it was that in May 1988, Jacques convened the seminar at Wortley Hall, a sumptuous mansion owned by a collective of trade unions. Among the people who took part were Hobsbawm, Hall, Campbell, and Moore (“I said: ‘Oh, that’s nice – a weekend away in a country house’. They said: ‘It’ll be £180 each’”). Also in attendance were two twentysomethings who were new to the magazine. Charles Leadbeater was a one-time researcher on the ITV current affairs programme Weekend World – where he had worked alongside Peter Mandelson – who had then moved to the Financial Times, and begun enthusiastically writing for Marxism Today, as well as joining the CP. “I said to Martin, ‘How do you get involved in Marxism Today?’” Leadbeater recalled. “He said: ‘Well, you really have to join the Communist party. And I thought: ‘Sod it. Alright, I will.’” Alongside Leadbeater sat Geoff Mulgan – not a CP member, but another new discovery who had begun his post-Oxford career at Livingtone’s GLC, before completing a PhD at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he shared the company of people working on the nascent internet. He would soon start work as an adviser to Gordon Brown.

The weekend’s conversations were sometimes difficult. When Leadbeater presented a paper about the modern expectation of choice and the need for the left to understand individualism, Hobsbawm seemed scandalised. “I went for a walk,” Leadbeater told me, “and after lunch, Eric came back and said: ‘It’s good to come to places like this and have debates, but I think we went a bit far this morning.’” Beatrix Campbell also recalls clashing with Hobsbawm thanks to what she saw as his antediluvian attitude to the women’s movement: “He was terrible on feminism. Awful … he was the kind of person who … will make you feel crap.”

The discussions led to a special issue titled New Times, published that October. “The uptake was fantastic,” Jacques told me. “There were articles in newspapers about it. Extracts were published. This was a major point of departure.” The central idea was “post-Fordism”, a term that captured western societies’ transition from what an opening editorial characterised as “mass production, the mass consumer, the big city, big brother state, the sprawling housing estate, and the nation state” to a new reality of “flexibility, diversity, differentiation, [and] decentralization”.

The term “Fordism” – a reference to that 20th-century kingpin Henry Ford – came from Gramsci, but the concept had been updated in 1970s by a group of French Marxist economists known as the Regulation School. In its British incarnation, the idea of post-Fordism was the work of an economist called Robin Murray – another thinker who had cut his teeth in the tumult of 1968, and who based his thinking in the real world, rather than theoretical abstractions.

Murray had played a key role at Livingstone’s GLC, where he worked as the grandly titled director of industry, and set up the Greater London Enterprise Board, aimed at giving the council an active role in the capital’s economy. At first, he and his colleagues had decided only to work with companies larger than a minimum size, thinking that Thatcherism’s fetishisation of small business was something to oppose. But when they took control of a bankrupt furniture factory in the Lea Valley that had 1,000 workers, they discovered it was being trounced by competitors in Italy – whose businesses were far smaller, did not have huge production lines and often worked co-operatively.

This realisation led them to immerse themselves in a new world of so-called flexible specialisation, and industries increasingly organised along much more agile, fast-moving lines, not least in retailing. When they worked with people from London’s music industry, the upshot was even more obvious: even if Fordism still defined large swaths of the world, in the late-20th century’s leading economies, Henry Ford’s world of vast production lines and standardisation – which had arguably been tested to destruction in the Soviet Union – was clearly on its way out, and this conclusion had huge implications for politics. “The forms of organisation – the Labour party, the trade unions, all these things – had all been formed around the same model as the corporate innovations we’d had in the early part of the century,” Murray told me. “It was all Fordist. So another theme was a critique of those structures, and how you could have much more open, democratic forms.”

Today, Geoff Mulgan – who was a protege of Murray at the GLC – calls his old mentor “the great unrecognised prophet of Britain. People like Hall and Hobsbawm are famous, but in many ways, Robin better understood where the world was going.” Now 75, Murray still brims with enthusiasm and insight: when we spent two hours together in a cafe next to the London School of Economics, he talked with infectious passion not just about the work he did for Marxism Today and the GLC, but his trailblazing efforts in what we now know as fair trade, and the nitty-gritty of environmentalism.

With Jacques’ help, Murray poured his thoughts into an article titled Life After Henry (Ford). As well as the economics of post-Fordism, he wrote about its political manifestations: not least, a new politics of consumption, rather than production (“the effects of food additives … the air we breathe and surroundings we live in, the availability of childcare and community centres, or access to privatised city centres”). He talked about what we would now call the “work-life balance ”. He emphasised the need for decentralised public services and structures of government. He pointed out that post-Fordism was widening the gap between the job market’s winners and losers, and that any future Labour government would have to “put a floor under the labour market, and remove the discriminations faced by the low-paid” (it would be another decade before the introduction of a British minimum wage). And he asked profoundly difficult questions to people still attached to the idea of jobs-for-life and the postwar settlement: “How real is a policy of full employment when the speed of technical change destroys jobs as rapidly as growth creates them?”

This was one of the best texts the magazine ever published. Murray had drafted it while on holiday in the Lake District, sporadically discussing it on the phone with Jacques and receiving requests for rewrites via the postman. “We had three weeks away,” he told me. “And I spent the whole time working on it. On the way back, we broke down. The AA had to come. It was two in the morning. And my wife has a picture of me at some service station, sitting on a suitcase, correcting this document.”

***

In late 1989, as communist Europe underwent a series of largely peaceful revolutions, the “tankies” were in abeyance, and the politics of Marxism Today dominated what remained of the CPGB, whose membership was now down to around 7,500. A new party mission statement, titled Manifesto for New Times, was being put together. Here were the ideas of New Times – indeed, the whole project pursued by MT over the previous 12 years – in the form of programmatic politics. The manifesto made the case for proportional representation, a written constitution, a strong emphasis on environmental sustainability, the possibility of an English parliament, a guaranteed citizens’ income, “the potential of information technology to decentralise and strengthen local control”, and the writing-off of developing-world debt – and had a prophetic view of Scotland, where “a new confidence” and “aspiration for self-determination” were emerging.

Jacques explained these ideas as the keynote speaker at the party’s annual congress, but by that point, it was clear that the CPGB was expiring, at speed. As Campbell put it, the new dominance of Marxism Today thinking in the party represented “a triumph over a corpse”. With its characteristic chutzpah, MT commemorated the end of European communism with a cover featuring an iconic portrait of Marx splattered with eggs and tomatoes. And it carried on for another two years, soon negotiating its financial independence from the party.

Having run a brief piece by Gordon Brown [pdf download ] about the New Times agenda in late 1989, it then carried an article by the Labour party’s shadow employment spokesman, one Tony Blair. “He rang me one day,” Jacques told me. “He said, ‘I’d like to write for Marxism Today – would that be possible?’ I worked on what he wrote with him; it went through several drafts. What’s the lightest boxing division? Featherweight. It was lighter than that.”

Blair’s piece appeared in October 1991, titled Forging a New Agenda . It suggested he had done a speed-reading of the Marxism Today canon, and then regurgitated it in the form of political nothings: “The notion of a modern view of society as the driving force behind the freedom of the individual is in truth the implicit governing philosophy of today’s Labour party.” In retrospect, it also suggested the magazine was running out of momentum.

Two months later, just as the Soviet Union ceased to exist and the CPGB wound itself up, Marxism Today published its last issue. Apart from anything else, Jacques told me, it was finished off by the leaden weight of its associations with communism. “After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the atmosphere was very triumphalist, and if you’d been associated in any way with the 1917 project, or Marxism, you were dead. It was very difficult to escape that. But also, I just wanted to stop. I was exhausted. I’d been worn out by it, and as wonderful as it was, I was feeling trapped.”

There was one last weird twist: in November 1991, the Sunday Times discovered old Soviet papers which revealed that, contrary to its leaders’ claims that the CPGB had struggled through the 1970s with no help from the USSR, at least two secret payments had been made to the party’s former assistant general secretary, Reuben Falber , who had kept some of the money in the loft of his bungalow in Golders Green. Jacques says he instantly resigned his membership; Campbell is not sure there was any party left to leave by this point. “I’d been assured that that in my political lifetime, we’d never taken any money,” said Jacques. “For me, it was an act of betrayal.”

“I still remember the moment when Martin rang me,” Campbell told me. “He said: ‘Are you sitting down?’ And then he told me. It was a scalding shock. Because our raison d’etre in the Communist party was that something in this revolutionary project could be redeemed. And the discovery of this sordid distribution of Soviet money … what it revealed was that what we had tried to do in the 70s and 80s had all been impossible. There’s no way we could have been allowed to win.”

Thatcher had been toppled by a Tory revolt in 1990, but the Labour party went on to lose its fourth consecutive general election in April 1992. Meanwhile, Jacques and Turner spent a year working on a possible successor to Marxism Today. It was to be a monthly magazine with an international focus; the working title was Politics, but it came to nothing. Jacques then helped Geoff Mulgan set up Demos , the thinktank that would attach itself to New Labour and supply it with no end of policy ideas. After a spell spent writing for the Sunday Times, Jacques then became deputy editor of the Independent between 1994 and 1996.

When Tony Blair became the leader of the Labour party in 1994, Jacques initially dispensed warm words. But three weeks before Labour’s great victory at the 1997 election, he and Hall announced in a piece for the Observer that, before the party had even taken power, it had been pushed in completely the wrong direction. “Blair embodies the ultimate pessimism – that there is only one version of modernity, the one elaborated by the Conservatives over the last 18 years,” they wrote. “He represents an historic defeat for the left, the abandonment of any serious notion that the left has something distinctive to offer.” The whole point of New Times, as they saw it, was to understand the new world and then set about challenging its injustices with a fresh kind of left politics. New Labour had attempted the first part, but replaced the second with a doctrine of surrender.

The seeds of this swingeing take had actually been planted nine years earlier – when Hall and Jacques warned in 1988 of the danger that Labour would “produce, in government, a brand of New Times which in practice does not amount to much more than a slightly cleaned-up, humanised version of … the radical right”. All this came to a head in November 1998, when Marxism Today returned with a one-off issue on “the Blair project”, preceded by another two-day seminar. The old typefaces and in-jokes returned; on the cover was a photograph of Tony Blair, and the word “Wrong” .

Marxism Today had floated policy ideas that New Labour had taken up. Blair and Brown had written for the magazine, and were now being advised by ex-Marxism Today writers. But its writers and thinkers now wanted to kill the idea that the magazine had anything in common what the government was up to. Citing the Asian financial crisis that had begun in 1997, Hobsbawm perhaps got a little ahead of himself, and wrote a piece charging Blair and Brown with “not recognising that the age of neoliberalism is over”. And in a long essay titled The Great Moving Nowhere Show, Hall harked back to the magazine’s peak, arguing that while Blair had touched “the modernising part” of Marxism Today’s ideas, he was “framed by and moving on terrain defined by Thatcherism”.

Mulgan had gone from Demos to a job as the head of Blair’s Downing Street policy unit. He also attended the MT seminar on Blair – and wrote an irate piece published in the one-off issue. “I was really annoyed with them all,” he said. “I thought they were deeply indulgent, and in their comfort zones: tenured academics, pontificating from on high.” At this point, he fell out with Jacques. “I haven’t seen him for years. He thought I’d betrayed him.”

All that apart, Mulgan is now candid about the gap between what people like him had envisaged and what Labour actually did with power. The first article he had written for Marxism Today – published in December 1988 – was titled The Power of the Weak. “Governments,” it said, “remain quintessentially strong power structures, devising policies and programmes at the top and passing them down to through a hierarchical bureaucracy to the people at the bottom.” When we met earlier this month at Nesta – the gleamingly futuristic “innovation charity” he runs in London – he agreed that New Labour’s record turned out to be a case in point. “There was the Mandelson view of what a party should be, which was very centralised and top-down: Leninism plus Saatchi-and-Saatchi advertising. One of the things we failed to do was to get a really active debate going about the shape and nature of the state. Tony Blair’s instinct was more, ‘Get some levers and pull them from the top.’”

“One of the dynamics of New Labour was, ‘You’ve got to change, because the world’s changing. If you don’t do it, you’re going to be out of a job,’” said Leadbeater, who worked as a government adviser in the early New Labour period, assisting Mandelson at the Department of Trade and Industry, and writing speeches for Blair. “They used that to get change in the party. But that was combined with two things. One was a notion of branding, and discipline. But also, there was something that developed in the first term.” This, he said, was a mixture of modern management consultancy and “the Brownite big state”, and it amounted to “super-Fordism … very mechanistic, and about setting targets. It didn’t become a bigger story about Britain. It was about delivery .”

“I remember going to an awayday with Blair and his policy team at Chequers, about two years in,” Leadbeater told me, “and saying, ‘The state can’t solve everything. If you think social goods are going to be represented by state spending, you can’t work that way now. You have to imagine how people can create social solutions in a different kind of way, with a different kind of state.’ They were interested. But actually, if you’re there in the middle of government, it becomes about pulling all these levers.”

He then turned his thoughts to more recent developments. “What if when Blair left office, you’d had a new generation of politicians who were capable of taking it all to a different kind of place: reasserting ethical values, being modern, but also embracing a more participative, open, decentralising kind of politics? Why wouldn’t that have been possible?” His face darkened, and he answered his own question. “It wouldn’t have been possible within the New Labour framework … and all that younger generation” – a reference to politicians such as the Miliband brothers, Yvette Cooper and Andy Burnham – “were schooled in that way of thinking”.

***

I met Leadbeater in an elegantly shabby cafe on Highbury Corner in Islington, north London, where we spent 90 minutes considering the Marxism Today legacy, and the real-life politics he now saw echoing the ideas MT had explored. “I see it in cities: in London, Manchester, Leeds,” he told me. “I see it in social media politics; in that huge response to the refugee crisis. I see it in the wave of people who want to be social entrepreneurs, and the soul-searching of lots of people involved in capitalism who think it’s in crisis. I see it all over the place. Just not in the Labour party.”

A few days later, he sent me an email containing an off-the-cuff text he had written about the rise of Jeremy Corbyn. “At first sight, it might seem strange to think that a politician who has not changed his views since the late 1970s might be an innovator,” Leadbeater wrote. “Yet that is what Jeremy Corbyn has managed to become while appearing blissfully – and, to some, charmingly – uninquisitive about the changing world around him.” He went on: “Corbyn has created what Roberto Unger, the Brazilian political philosopher, calls a ‘high-energy’ politics – tumultuous, passionate, participative, dynamic, unfolding … It’s just possible that some of what Corbyn and his young team might try – open-sourcing questions for PMQs, involving the party in constant rolling debate – might work by being more participative than old-style politics … So the lesson in all of this is perhaps above all not to be sniffy, not to turn our noses up and not to make assumptions, but to learn, and fast, about what Corbyn, the unlikely innovator, is telling us about the world.”

Other Marxism Today alumni were pessimistic. One pointed out that, as a Haringey borough councillor and then London MP, Corbyn – a regular contributor to the Morning Star – was party to the leftwing tumult in the capital that blurred into Marxism Today and the GLC. The new shadow chancellor John McDonnell, indeed, served as the GLC’s deputy leader. But, they said, “the good bits of the GLC were essentially ’68 politics. And the weird thing about McDonnell and Corbyn is that they were almost pre-that: culturally untouched by the 1960s.”

“If Corbyn was a woman of 35 or 40, we’d be in business,” Robin Murray told me. “But he’s missing 100 tricks. I wish he’d speak about the future, not the past.” He gestured at the copies of Marxism Today I’d brought with me. “And I wish he’d take things out of all this. I suppose my hope is that he listens to young people, because he believes in democracy.”

“Corbyn is, in a way, a throwback,” Jacques told me. “But his message seems more relevant than it did then.” For a moment, I got a sense of what it would have been like in one of those Marxism Today seminars, throwing around ideas and arguing for the fun of it – as Campbell put it, thinking, thinking, thinking. “You can’t just extrapolate from the past and think in straight lines: that’s what I learned from Gramsci,” Jacques said. “I thought the Labour party was dying, and I don’t think that’s true now. In some measure, it’s being revived.

“There are ironies there, but I quite like them,” said the man who mapped out the future from inside the doomed British Communist party. “It shows you we’re in a new period.”